By Tommie Gorman

Outside of Sligo, the story of our King Billy is not widely-known. He came south during some of the worst years of The Troubles.

Nobody knows who actually invented the phase ‘make love, not war’ but Billy Sinclair relentlessly carried out his own grafter’ version of the same.

In Billy’s case, the love involved was his passion for football. He was single-minded about it. He was the Protestant who had played with distinction for Linfield and Glentoran (and had a short spell with Chelsea). He then crossed the border – at a time when there were checkpoints and real danger – and he took a job as player manager of Sligo Rovers. He then micromanaged our club to its first League of Ireland title for 40 years.

Last Tuesday night’s BBC NI’s Newsline programme, reporter Michael Fitzpatrick told how Billy Sinclair now has dementia. Just days before it was confirmed the former Scotland, Leeds and Manchester United defender, 68-year-old Gordon McQueen, was diagnosed with the same condition.

Billy is 74 now. His son, Jonathan, is backing calls for diseases like dementia and Azheimer’s in ex-players to be deemed an industrial injury. Two years ago research conducted by the Football Association and the Professional Footballers’ Association found that former footballers are three and a half times more likely to die from degenerative brain diseases than non-sporting members of the general public.

Jonathan Sinclair makes the case for people like his father to be entitled to better welfare support. The consultant who diagnosed Billy Sinclair’s condition felt heading the ball during his long life as a footballer was a contributory factor.

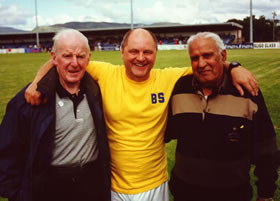

I knew Billy Sinclair in his prime. He was meticulously building the components that would deliver a League of Ireland title to a club not used to success. I was a reporter, starting off, delighted to be following his every move.

He was small and stocky. He wore a sheepskin coat and he had the presence to fill a room. He managed Sligo Rovers down to the finest detail. He knew what was needed to survive and prosper.

On the team bus heading for Waterford he gave each set of two players a pound and let them off at the Italian chip shop in Athlone. That night some of the squad broke curfew and were in the disco having their first beers when ‘Wee Sinkie’ pounced. The fines were dished out in his rasping accent and the sorry bunch headed for bed like small boys. The only one to escape sanction was Tony Fagan. He had spotted Sheriff Sinclair from several hundred paces and was gone for dust.

Billy was on the job day and night. He introduced a Golden Goal scheme on match days – a fund-raising venture he’d known in a former club – and it helped to provide much-needed revenue. He persuaded a former Northern Ireland international goalkeeper, Alan Paterson, to come south. He signed young players who had been let go by English clubs from lower divisions and persuaded them they were too talented to give up.

One of his trump cards was a local teenager, Paul ‘Ski’ Magee. Billy had seen enough of football to realise the young striker had the potential to follow his dreams elsewhere.

Under Sinclair’s management Magee became a star and would eventually sign for Queen’s Park Rangers and progress to become a fully-fledged Irish international. Ski and the current Everton captain, Seamus Coleman are Sligo Rovers most famous players of modern times.

Billy could also be fun when he occasionally let down his guard. His wife, Bonnie, was a hoot. He was always trying to make his team the best it could be. One of his most skilful players had a fondness for drink. Before big games, Billy got him access to a concoction known as ‘anti-booze’ that would make him physically sick if he took alcohol.

At one stage Rovers had a serious lack of a creative midfielder. Billy located one up North. He had a huge tattoo on his chest that made it clear he understood the concept of July 12th Orange parades. Politics were set aside inside and outside the dressing room and the said player did his talking, and his marching on the pitch.

The Showgrounds Rising under King Billy took place on Easter Sunday 1977. Deliciously, a victory over Shamrock Rovers was required to pip Bohemians for the title. Children were sitting on the grass inside the fencing of the overcrowded ground. The late Paul Magee, son of the famous RTÉ commentator Jimmy Magee, scored for the visitors but Sligo got three.

The atmosphere of those times is so beautifully captured in the recent documentary ‘Shine’, available on You Tube.

Dreams reached a new orbit that September when Billy Sinclair brought his team behind the Iron Curtain for the first leg of the European Cup clash against Belgrade. He was 30 at that stage. A battle-scarred 30. Nevertheless he selected himself to play as sweeper because he knew the Yugoslav champions, including several internationals, had the firepower to give Sligo Rovers an embarrassing hammering.

Once more borders and politics became meaningless. The late and great man the with magic sponge, James Tiernan, didn’t travel. Billy sent for an old friend from the Linfield dressing-room to help prepare his charges.

The park the bus tactics worked a dream until the 60th minute when Red Star drew blood. But Billy’s side kept going and going. The final score was 3-0. One of the most memorable moments involved Sligo Rovers midfielder, Tony Fagan.

So many times on the muddy Showgrounds pitch, Fago tried a drag back that he learned as a street footballer at the weighbridge near Saint Brigid’s Place. In the Red Star stadium Fago tried it one more time and left two players on their backsides. The huge crowds applauded. Fago was surprised but then delighted. He put his foot on the ball and waved.

That Red Star side included the wonderful winger, Dragan Dzajic; defender Nikola Jovanovic who later signed for Manchester United and Vladislav Bogicevic who was eventually allowed to join the New York Cosmos and became a member of the American National Soccer Hall of Fame.

I had covered most if not all of the games during that League-winning season and the ancillary activities but I had rarely seen Billy let his hair down. He did so that night in Belgrade. There was a party for a few hours in his room. It was behind the Iron Curtain and pre slabs of beer times.

But the drink flowed. The Sash got an airing. Some of the young English lads had a verse of two of Beatles numbers. The Sligo crew chipped in with a few out of tune verses.

It was more than 43 years ago and it was a lovely time to be alive.

Billy Sinclair may or may not remember how good he was then.

But those of us who saw him going at full tilt will never forget him.

He made such a difference to our club. To our town. To our lives.

Sligo Rovers have spoken with the Sinclair family to offer our support at this time